Tagged: Steven Offenbacher

Some Remarks on “100 Years of Progress in Periodontal Medicine” (II) – Diabetes Mellitus

ISTOCK/MTHIPSORN under fair use.

That periodontitis and diabetes mellitus are related is known for more than 100 years. While Beck et al. (2019), in their contribution to the JDR Centennial Series on 100 Years of Progress in Periodontal Medicine, start out with a paper by Williams and Mahan (1960), which is mentioned as the first landmark paper (allegedly the first study showing that periodontal therapy reduces insulin requirement; but this study had only shown that removing all teeth with advanced decay improved glycemic control), the latter authors quote a booklet by Otto Georg Grunert of 1899 a patient guidebook for diabetics: Ueber Krankheitserscheinungen in der Mundhöhle beim Diabetes: Therapeutische Winke für Diabetiker. In particular the medical profession had known about the link of diabetes mellitus and oral disease for long.

Further landmark, or “milestone”, papers in Beck et al.’s list on the diabetes-periodontitis relationship appeared around 1996, when late Professor Robert J. Genco, for the first time, had used a slide with the message, Floss or Die! on the occasion of the annual meeting of the American Academy of Periodontology in New Orleans. Some of these studies indeed sparked the idea that it would be possible to reduce HbA1c, the marker of diabetic control, by proper periodontal treatment of diabetic patients.

Some Remarks on “100 Years of Progress in Periodontal Medicine” (I) – Cardiovascular

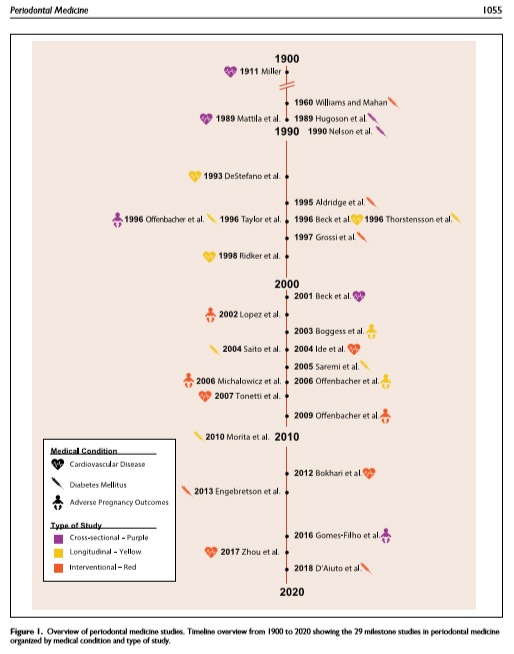

In its “Centennial Series”, an article celebrating Periodontal Medicine appears in next month’s issue in the Journal of Dental Research. The authors James Beck, Panos Papapanou, K.H. Philips and late Steven Offenbacher scrutinize a number of so-called landmark, or “milestone”, studies regarding three pathologic conditions, cardiovascular disease, diabetes mellitus, and adverse pregnancy outcomes. As in every opinion piece, one needs careful reading in order to identify the authors’ bias [1].

Cardiovascular disease

The authors recapitulate the timeline beginning with W.D. Miller’s dental focal hypothesis of 1891. (When writing, I couldn’t get full access to the Lancet article of 1891 to which Beck et al. originally refer.)

They then turn to the stunning (then) observation by Finnish authors Mattila et al. (1989) who adopted a “dental index” of caries, marginal and apical periodontitis, and pericoronitis in a case-control study of hospital admitted patients with recent myocardial infarction and matched controls from official records inhabitants of Helsinki. These authors had set up a logistic regression model adjusted for traditional risks, in particular smoking (former and current smokers) and identified the “dental index” (as well as smoking and, negatively, HDL cholesterol) being statistically significantly associated with myocardial infarction (Odds ratio 1.2586, 95% confidence interval 1.1503; 1.3771, my calculation based on given coefficient and standard error estimates). In two subpopulations, medians of the dental index were 4 and 6. So, the observed odds ratio for increase of 1 score in the index (1.2586) must in fact be considered substantial. This was a single center, low quality (as of current standards) case-control study which had to be confirmed in larger observational and ultimately interventional studies.

The Literature That Shaped Modern Periodontology (V)

I have written about AAP’s centennial and the series of papers celebrating the “literature that shaped modern Periodontology” in several posts, see here and here. In this month’s contribution (in the Academy’s Journal of Periodontology), Steven Offenbacher and James Beck attracted my attention when writing about “Changing Paradigms in the Oral Disease–Systemic Disease Relationship.” Twenty-five years after the first report by Finnish researchers on a certain risk of poor oral health for cardiovascular disease, the incredibe surge of studies all over the world (“Floss or Die!”) may have ceased, paving the way for another overdue paradigm shift.

The paper disappoints. Instead of putting the initial and long-lasting exciting in at least some relation in view of results of recent very large intervention studies which were by and large not able to confirm a postulated beneficial effect of treatment of periodontal disease on cardiovascular disease, low birth weight or diabetes, Offenbacher and Beck opened the bottom drawer and pulled a couple of now questionable studies which, well, misled the public and thousands of researcher worldwide alike. For instance, Frank De Stefano’s paper of 1993 who, based on NHANES I follow-up data, reported a 25% increase of risk in patients with periodontitis. The data had been re-analyzed by Phillipe Hujoel in 2000 including much more careful adjustment of cofounders. They could not find an association. I have reported about the apalling letter to the editors of JAMA by Robert Genco and colleagues here.

And then, of course, the paper by Beck et al. (1996) from the VA Longitudinal Study.

“Our paper showed that periodontal disease was a significant independent risk factor for CVD events after adjusting for traditional risk factors and displayed a dose-dependent increase in risk with increasing periodontal disease severity. Importantly, this paper described a two-component mechanistic working model that linked periodontal disease to cardiovascular disease via systemic bacterial dissemination interacting with the vasculature and activation of the hepatic acute phase response as an inflammatory trigger for CVD. We also hypothesized that there may be an underlying hyperinflammatory trait that served to increase risk for both conditions, suggesting that bacterial exposure in those susceptible individuals would result in even more risk for CVD. In addition, by placing importance on inflammation, it explained how oral infection could influence multiple conditions such as diabetes. Over the next 10 years, many studies supported this basic model. The model is now more than 15 years old, and we would modify it only by adding specific details, such as the hyperinflammatory trait likely being attributable to genetic differences in the innate immune response.” (Emphasis added.)

How It All Began

Readers may have noticed my dismay about our “thought leaders'” recent attempts to revive the perio/systemic issue despite emerging evidence of no or very small, irrelevant, effects of periodontal treatment in large-scale intervention studies on HbA1c in type 2 diabetes, or pregnancy outcomes.

I had yesterday discussed via email with a critical mind in the U.S. the results of another intervention study on cardiovascular events which never made it beyond a pilot study, the Periodontitis and Vascular Events, or PAVE, study. Since periodontitis patients were not randomized according to whether they received periodontal treatment but according to a community comparator (referral to community dentist with copy of x-rays and letter with diagnosis and recomendations for treatment), I had argued that such a design would not fulfil criteria of an RCT since patients who get proper periodontal treatment in the comparison group may fundamentally differ from those who won’t care. However, patients who won’t care in the test group would get the treatment anyway. So, interpretation of biased results would be difficult if impossible. Not surprising, the PAVE study did not get funding after the pilot phase (Beck et al. 2009) [pdf], which resulted in non-significant differences anyway, possibly (but not inevitably) due to lack of statistical power.